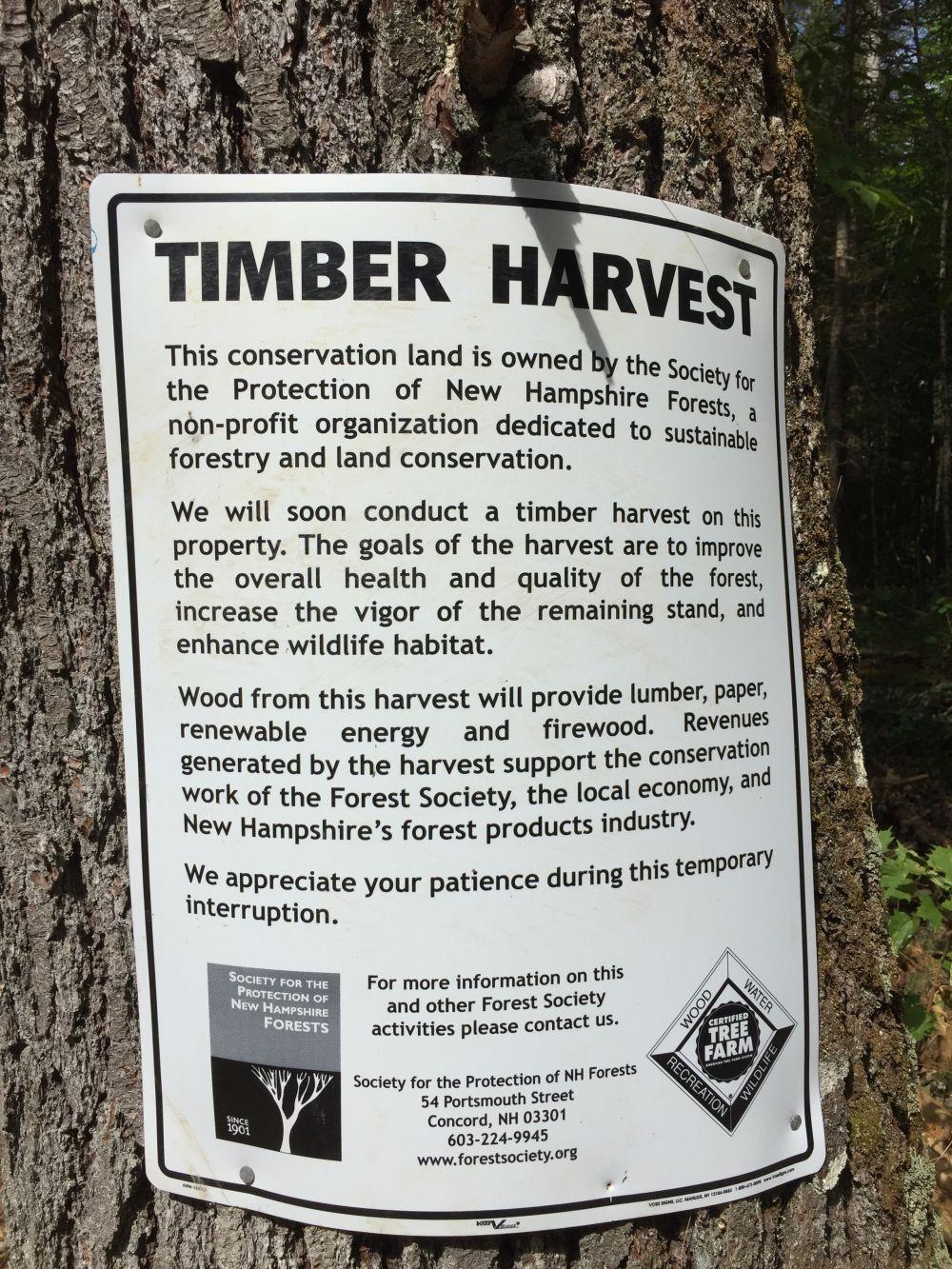

Timber harvest at the Forest Society Crider Forest in Stoddard, NH

Many people don't think of trees when we speak of "harvest." Corn is harvested; apples, tomatoes, squash are the fruits of the annual autumnal rite which is the province of our farmers. Maybe it's because those plants are harvested at the end of their lifespan that we don't lament the moment they are cut down. We're much more precious with our trees.

Maybe because we associate de-forestation with developments of housing sub-divisions, or banal strip malls with all the character and scenic beauty of sound baffles on the sides of our highways. But, as a society we consume forest products as much as we do farm products. And sometimes when a tree comes down it's not to make room for another human edifice, but another tree.

The Forest Society's Dave Anderson and Wendy Weisiger took NHPR "Something Wild" Producer, Andrew Parella us to The Crider and Rumrill Forest Reservation in Stoddard, NH where that is the precise plan: taking down trees to plant the next forest.

We started at the landing at the Crider and Rumrill forest where the logs are being piled for a tractor trailer to haul them away to mill and market. There's crushed stone in place to cushion the arrival of logging trucks. There are piles of freshly cut logs: spruce, hemlock, pine, fir - these are soft woods. There's an overwhelming smell of pine pitch and sap on this summer morning.

Most of the logs on this landing are soft woods and will be turned into dimensional lumbers (2x4's) for the construction industry. And keeping an eye on the ever growing piles is Jeremy Turner, forester with Meadowsend Timberland.

While the Society for the Protection of NH Forests owns the land, they contract Turner to help them maintain the forest and manage this type of harvest. The job of the forester is far more nuanced than tying surveyors tape around trees, as Turner explains it's a careful balancing act of understanding the mission of the land owner, and the ecology of the forest (there are many types of forest and each requires slightly different stewardship); finding the right logger for the job and communicating with him how to best access the trees for harvest (which parts of a land parcel to avoid, like wetlands).

Turner explains that part of mapping out the route for the logger is also to identify "seed trees," these are the trees that will re-seed the area after the harvest, to create the next forest. To help those seeds take root, Turner is "trying to manipulate light" in selecting which trees to harvest. "Because there are existing small seedlings in place which need a high level of sunlight."

If Turner is the doctor, writing the prescription for managing the health of this parcel of land, Todd Carmichael is the pharmacist who fills that prescription. Carmichael is logger with 30 years experience, now with High Tech Harvesting. His job is to remove the trees that Turner has marked and transport them to the landing.

High tech, indeed. We're a far cry from the days of the two-man cross-cut saw. "It's a lot easier now than with a chain saw." Carmichael who began his career when the chain saw was the tool of the trade. The mechanized head on the boom of his CAT harvester is an impressive bit of engineering. The saw that makes the initial cut to fell the tree, the gears that push the trunk of the tree through the head, the knives that pop out to de-limb the tree, the measuring wheel, and the saw that cuts the logs to length are all control from a digital display in the air-conditioned cab.

The limbs of the trees are left on the forest floor to protect the logger from mud, and protect the ecosystem from the machines. Carmichael leave the cut logs in a pile by the side of the trail for the forwarder, which takes them out to the landing.

Carmichael fires up the harvester for a demonstration, "when I get up to a tree, I can cut a tree down and have it processed into a pile in a little over a minute."

As quickly as it might come down, Turner knows what he wants this forest to look like in twenty years time, "I'd like this forest to be vibrant, dynamic, stable from a biological standpoint. So diversity of species blends, different age classes of trees and different forms of biology."