- Tags:

- Wildlife,

- Something Wild

The fisher - not a cat, a member of the weasel family

Fisher populations are down, there’s consensus among wildlife biologists at least about that much...

But why that is happening is open to debate, as is what to do about it.

At Something Wild, we sat down with a couple of wildlife biologists recently who disagree; Meade Cadot, former Executive Director of the Harris Center for Conservation Education, and Patrick Tate, leader of the state’s fur-bearer project for NH Fish and Game.

We started with a quick refresher on the biology of the species we’re talking about. One of the largest points of confusion is what the species is called. As Cadot points out the only Fisher Cats in New Hampshire are in Manchester, there’s a roster full of them. The species we’re discussing here is fisher; they’re not cats, they’re actually part of the weasel family.

Fishers are also smaller than you’re imagining, Cadot explains, “a big male fisher is about the size of a fox. It’s got shorter legs, shorter nose and bigger feet.”

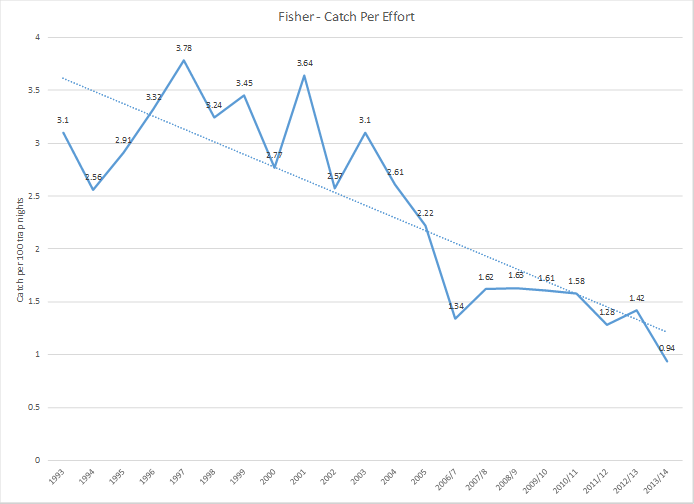

Fisher is also a game species, with a global market for their fur, which is mostly used for trim on jackets and coats. So there is a trapping season for fisher. And trapping season is important, because fisher populations are extrapolated by the number of animals trapped. Tate points out that, “it’s not a census, it’s an index. It gives you an idea of the population on the landscape, but it doesn’t give you a population level.”

Most people agree that this index isn’t a great way to estimate the population, but conducting a full population survey is an extremely expensive process to send teams out to track and count an animal that prefers to remain unseen. A recent bobcat population survey cost Fish and Game $200,000. So it’s not great, but it’s what we got. And that’s where things get tricky, because this index has charted a steady decline in fisher numbers over the past 15 years.

Patrick Tate points out that our neighboring states are seeing a similar decline. “Maine has talked to us about their declines, Vermont has talked to us about their declines. The interesting thing is in the very southern edge of its range – Pennsylvania, Virginia, those places – they’re seeing [fisher] populations expand.”

But Cadot sees a pattern among states charting declines. “It seems to be localized in NH and ME, where trapping is most liberal.” Cadot also points to a study conducted by Maine Department of Inland Fisheries and Wildlife in the 1980s. “They had 76 fishers collared with radio-telemetry devices. And it turned out that 80-percent of the deaths they recorded were due to trapping. So that’s a good indication that trapping can be a major problem.”

But Tate suggests taking a step back and looking at the larger picture on the landscape. “Our marten population’s doing the best it ever has. Our bobcat population is shooting through the roof.” Martens and fishers are mutually antagonistic, and bobcats will simply eat fishers. So when marten and bobcat populations go up, you can expect to see fisher numbers go down.

Tate also weighs the evidence provided by longtime trappers who’ve seen this kind of decline before. “There appears to be a roughly 30-year cycle. So we’re in a low now and it’s my belief that in seven years or so we’ll see these numbers start to go the other way.”

But Cadot isn’t content to wait for the numbers to change on their own accord and is encouraging Fish and Game to take action to conserve the population, namely shortening the trapping season and limiting the number of animals trappers can take. “It worked before. When we did it, the fisher population responded.”

But even Meade concedes that this is a complicated matter. “There are so many other things that may be playing into what’s going on here.” And that’s the crux of it, there are many forces that could be affecting fisher numbers in the state. It’s precisely what makes wildlife management and stewardship such an imprecise science. Biologists collect what data time and resources allow them to. But any actions they take to benefit one species must be weighed against the effects those actions could have on the larger eco-system.