Floodplain photographer reveals beauty of Alders

Graceful alders grow in wetlands

Q: What tree common to the floodplain matches the following list of clues:

1. The city of Venice was built on pilings of its wood, which when submerged, becomes rock hard and rot resistant.

2. They concentrate minerals within their cells and are sometimes used for soil reclamation.

3. Native Americans used their bark for astringent teas for (among other things) toothache and difficult childbirth.

4. Its wood (along with a unicorn hair…) was used to make the wand of Quirinus Quirrel, Harry Potter’s first Defense Against the Dark Arts Professor .

Give up?

A: The Alder!

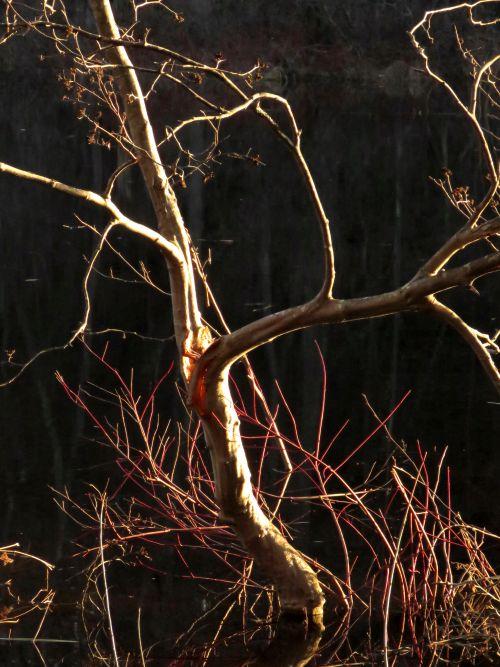

This is the time of year to best appreciate the graceful beauty of alder branches, before they have leafed out, and their bare forms hung with cones and catkins are most easily seen. Alder trees always make me think of art nouveau designs, limbs arcing away from their twisting trunks, angling this way and that in a web of tapering branches and twigs. But aside from the beauty of their form, the alder’s function in the web of riparian life is a significant one.

Alders thrive in wet areas and their roots, often partially submerged, help create the stream meanders that prevent erosion and provide a dark, still habitat for aquatic mammals and insect larvae. Because alders sprout roots along the length of their submerged, buried stems, thickets of these shrubs are created that provide dense cover for nesting birds.

Alder roots also have nodules that contain a bacterium that absorbs nitrogen from the air, in exchange for sugar provided by the alder tree through photosynthesis. Because of this relationship, the alder adds nitrogen to the soil, creating a more fertile environment for the surrounding plants and trees. Some of our most common floodplain songbirds have alder seeds as part of their diet, including chickadees, warblers and goldfinch. Twigs and branches of the alder feed our beaver population, who also use the tree extensively to build their dams and lodges.

Individually and in clusters, alders can be found all along the bank of the Mill Brook. Colin Tudge, in his book The Tree, drops the offhand comment that in their mineral concentrating capacity, alders “pick up gold, for instance. Whether it is worth trying to extract gold from them, I do not know.” I don’t either, but I do know that my appreciation for these common and lovely trees is heightened by the knowledge of what I can’t see: that dense tangle and mesh of roots submerged in shadowy waters, sheltering muskrat and mink, bright painted turtles and old snappers, fish, fly nymphs, middens of old mussel shells, decayed leaves, and the swirl of nutrients that support all of this life.